- Published on

Functions & Variables (Part I)

13 mins

- Authors

- Name

- Juleshwar Babu

Table Of Contents

- Recursion & Stack

- Rest Parameters & Spread Syntax

- Variable Scope & Closure

- Closure

- Dead Zone

- Content Updates

Recursion & Stack

The maximal number of nested calls in a recursion is called its recursion depth.

https://javascript.info/recursion#the-execution-context-and-stack

The execution context is an internal data structure that contains details about the execution of a function: where the control flow is now, the current variables, the value of

thisand few other internal details.One function call has exactly one execution context associated with it.

When a function makes a nested call, the following happens:

- The current function is paused.

- The execution context associated with it is remembered in a special data structure called execution context stack.

- The nested call executes.

- After it ends, the old execution context is retrieved from the stack, and the outer function is resumed from where it stopped.

Rest Parameters & Spread Syntax

The spread operator can be used in a function definition to collect all the incoming/rest of the arguments into an array. The dots literally mean “gather the remaining parameters into an array”.

function sumAll(...args) { // args is the name for the array return args.reduce((acc, curr) => acc + curr, 0) } alert( sumAll(1) ); // 1 alert( sumAll(1, 2) ); // 3 alert( sumAll(1, 2, 3) ); // 6https://javascript.info/rest-parameters-spread#the-arguments-variable

argumentsis an array-like object in a traditional function which has all the arguments by their index. Althoughargumentsis both array-like and iterable, it’s not an array.function logName(fName, lName) { for(let name of arguments) { **// Iterable** console.log(name) // "Daniel", "Naroditsky" } **// Array-like** console.log(arguments[0]) // "Daniel" console.log(arguments[1]) // "Naroditsky" // Not an array! **console.log(arguments.map) // undefined!** console.log("Hi I'm ", arguments[0], " ", arguments[1]) } logName("Daniel", "Naroditsky")https://javascript.info/rest-parameters-spread#the-arguments-variable

Arrow functions don’t have the

argumentsarray. If we try to access the array inside an arrow function, it takes the array from the closest traditional function parentDifference between

Array.fromand…Array.fromconverts both iterables and array-likes into an array. But…only converts iterables into arraysconst arrayLike = { 0: "A", 1: "B", 2: "C", length: 3 } const iterable = { from: 1, to: 4, [Symbol.iterator]: function() { return { current: this.from, last: this.to, next() { if(this.current <= this.last) { return { value: this.current++, done: false} } return { done: true } } } } } console.log(Array.from(arrayLike)); // ["A", "B", "C"] console.log(Array.from(iterable)); // [1, 2, 3, 4] console.log([...iterable]) // [1, 2, 3, 4] [...arrayLike] // Uncaught TypeError: arrayLike is not iterableWe can use

{code blocks}to isolate a piece of code that does its own task, with variables that only belong to it.{ // show message let message = "Hello"; alert(message); } { // show another message let message = "Goodbye"; alert(message); }

Variable Scope & Closure

https://javascript.info/closure#lexical-environment

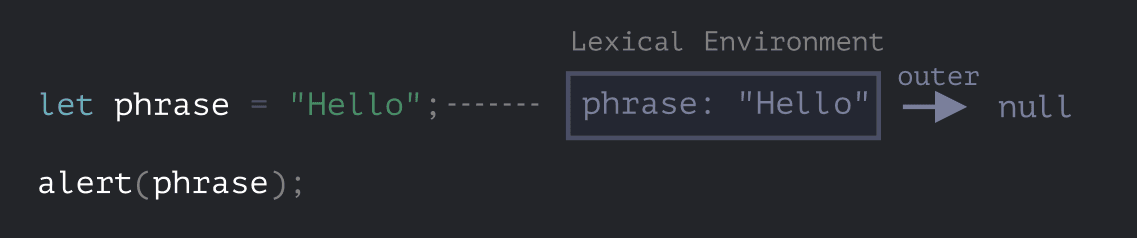

Every running function, code block

{...}, and the script as a whole have an internal (hidden) associated object known as the Lexical Environment. Theoretically, each function is supposed to have a[[Environment]]property which links it to its Lexical EnvironmentThe Lexical Environment object consists of two parts:

- Environment Record – an object that stores all local variables as its properties (and some other information like the value of

this). - A reference to the outer lexical environment, the one associated with the outer code.

Variables

A “variable” is just a property of the special internal object,

Environment Record. “To get or change a variable” means “to get or change a property of that object”.The outermost LE is the global LE whose outer LE is

null

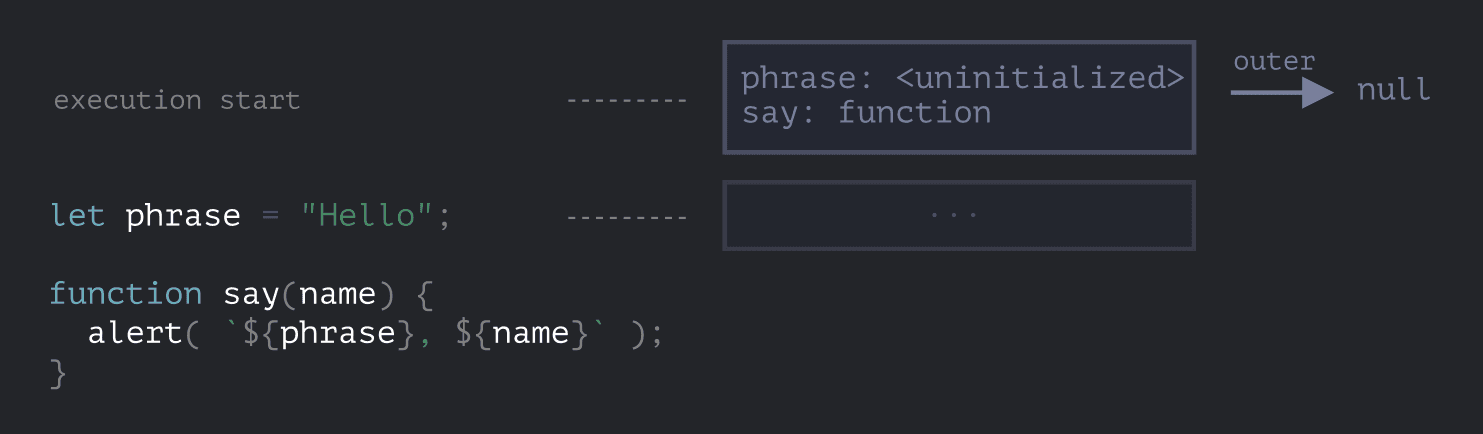

Function Declarations

A function is also a value, like a variable.

The difference is that a Function Declaration is instantly fully initialized.

When a Lexical Environment is created, a Function Declaration immediately becomes a ready-to-use function (unlike

let, that is unusable till the declaration).That’s why we can use a function, declared as Function Declaration, even before the declaration itself. #til

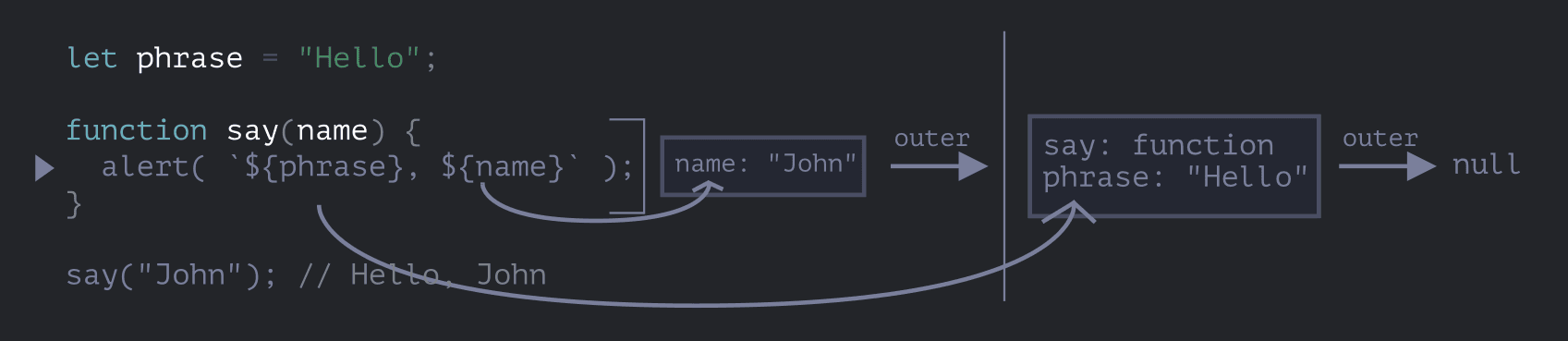

Inner & Outer Lexical Environment

When a function runs, at the beginning of the call, a new Lexical Environment is created automatically to store local variables and parameters of the call. #til

When the code wants to access a variable – the inner Lexical Environment is searched first, then the outer one, then the more outer one and so on until the global one. This is very similar to the how the prototype chain is followed to find a property.

Returning a function

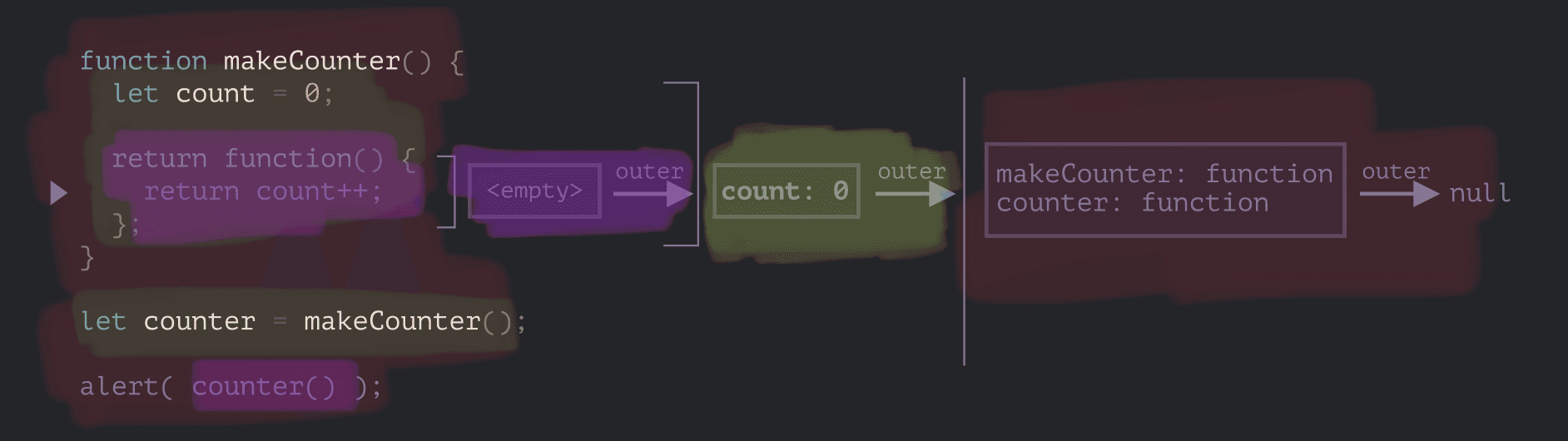

function makeCounter() { let count = 0; return function() { return count++; }; } let counter = makeCounter(); let counter2 = makeCounter(); console.log(counter()) // 0 console.log(counter()) // 1 console.log(counter()) // 2 console.log(counter2()) // 0Please refer to the image below while reading the content to get sufficient context as to what’s happening. Let me know in the comments if the content below needs further simplification/clarity.

At the beginning of each

makeCounter()call, a new Lexical Environment object is created, to store variables for themakeCounterfunction call instance.The execution of

makeCounter()returns a tiny anonymous function with only one line:return count++. We haven’t called it yet.So,

counterwhich refers to the newly created anonymous function has an[[Environment]]key (counter.[[Environment]]) which points to{count: 0}lexical environment. When a function is created, it also remembers where it was created! No matter where you call this function, it will always have a reference to its lexical environment. The[[Environment]]reference is set once and forever at function creation time.Later, when

counteris called i.ecounter(), a new Lexical Environment is created for running the one-liner anonymous function. That Lexical Environment’s outer points tocounter.[[Environment]]Now when the code inside the anonymous function i.e

counter()looks forcountvariable, it first searches its own Lexical Environment (empty, as there are no local variables there), then its outer Lexical Environment, where it findscountand thus modifies the value in that environment.A variable is updated in the Lexical Environment where it lives.

💡the

count: 0which is green highlighted becomescount: 1after execution ofcounter()

Closure

A closure is a function that remembers its outer variables and can access them. In JS, all functions are naturally closures (there is only one exception, to be covered in The "new Function" syntax).

That is: they automatically remember where they were created using a hidden

[[Environment]]property, and then their code can access outer variables.Dead Zone

// Variable is present but uninitialized function func() { console.log(someVal); // Uncaught ReferenceError: Cannot access 'someVal' before initialization let someVal = 1; } func();// Variable is present but uninitialized let someVal = 1; function func() { // First it checks the current lexical environment before checking the outer one. The variable is present but uninitialized console.log(someVal); // Uncaught ReferenceError: Cannot access 'someVal' before initialization let someVal = 2; } func();// Variable does not exist function func() { console.log(nonExistingVal); // Uncaught ReferenceError: nonExistingVal is not defined } func();In this example we can observe the peculiar difference between a “non-existing” and

<uninitialized>variable.A variable starts in the

<uninitialized>state from the moment when the execution enters a code block (or a function). And it stays<uninitialized>until the correspondingletstatement.In other words, a variable technically exists, but can’t be used before

let. This zone is called the dead-zone

- Environment Record – an object that stores all local variables as its properties (and some other information like the value of

Content Updates

- 2023-08-03 - init